Steven Gizicki

Formidable Grammy-winning and Emmy-nominated music supervisor, Steven Gizicki returns to discuss his contributions to the glamorous, tempestuous universe of FX’s Fosse/Verdon. He is the fanatic force of nature behind a myriad of feature films including Crazy Rich Asians, Arctic, Smallfoot, Operation Finale, Teen Spirit, Strange Magic, The Titan, Franca: Chaos and Creation, and the mega-hit technicolor musical, La La Land, which garnered six Academy Awards and seven Golden Globes. Starting in the music business as a soundtrack executive at PolyGram Records and a marketing principle at Virgin Records, Steven pivoted to serve as head of music at Lucasfilm, followed by an in-house music supervision position at Walt Disney Animation. Now a freelance powerhouse, Steven continues re-define his craft as showcased in the elaborate yet harmonious soundtrack of Fosse/Verdon. In our conversation, Steven speaks on faithfully replicating iconic cinema moments derived from the repertoire of Bob Fosse and Gwen Verdon, as well as his involvement in the upcoming film adaptation of hit Broadway musical, In The Heights.

Courtesy of Subject

Congratulations on your “Outstanding Music Supervision” Emmy nomination for FX’s Fosse/Verdon. This limited series examines the successes, heartbreaks, and power struggles within the creative and romantic partnership of legendary filmmaker/choreographer, Bob Fosse, and Broadway’s most exceptional dancer, Gwen Verdon. At the beginning of this project, what was the extent of your knowledge regarding Fosse and Verdon’s legacies?

My knowledge of them was, by all means, not encyclopedic, but I was really familiar with them because I’ve been a fan of Bob’s work for quite some time and same with Gwen’s. But once I got the job, I picked up Sam Wasson’s biography [Fosse] that the show was based on, and I just devoured that. I mean, the thing is larger than a telephone book and I just blew through it within the span of a couple of days — it’s so gripping.

After reading it, I realized that my knowledge of Bob and Gwen was just really surface level up until that point. I think the same goes for most people in the world, which is why I love Fosse/Verdon. This show highlights the moments that we all know, whether it’s Cabaret, Chicago, or all these iconic works that they created together — that’s the first thing you see when you walk in the door. But beyond that, there’s a whole house behind it of really fascinating personal experiences that are just larger than life, and larger than fiction. That’s what I thought was so engaging about the book — their real lives and stories read like a great novel if that makes sense.

Absolutely. It never occurred to me how much pain they went through behind the scenes of these incredible productions.

Right. It’s a complicated show. It was not on me to depict Bob [Fosse] to the world’s viewing audience, which was good because it was in the very capable hands of Tommy [Kail] and Steven [Levenson]. Bob was an incredibly complex character and not always likable. He’s not what one would call a hero, so to speak. He was great artist, but he had a dark side. I think the show did such a great job at showing the good, the bad, and the ugly of his world.

That approach seems more realistic in terms of representing the human condition. While watching the series, I thought to myself, “Man, one could call him a cad.”

And I think many people did. As you know, the show was just filled with so many re-recordings of those iconic film moments. During the recording process, there were a few times we were in the studio that one of the musicians would come up to me, and he would say, “You know, my wife used to be one of Bob’s dancers.” And I just thought, “Oh, no. I’m not going to ask any questions.”

Times have changed, and we’re living in the #MeToo era. I know it was a big discussion at the outset of the creation of the show because certain behavior that was excusable in the ’70s is not excusable anymore. Thank goodness for that. I think the writers did a great job at presenting Bob Fosse’s story in an honest, sort of unapologetic way. They didn’t make any excuses [for his actions], and it’s done very well.

As you acclimated yourself to their intertwined stories, what themes in Sam Wasson’s Fosse spoke to you personally?

In terms of what I love about their stories, Bob and Gwen were two just incredibly creative, brilliant people who were far ahead of their time. In a sense, the two of them combined were larger than the sum of each of their parts. Neither one of them could have accomplished all of this without the other — that’s what the series shows you.

When Bob is trying to film Cabaret in Berlin and Gwen isn’t there in person, he sort of falls apart, so she flies out and together, they find the solutions. So that’s what I found really interesting because the book is really not so much about Bob and Gwen — it’s more about Bob. The show is really about the two of them, and I just loved that it focuses on what they’ve created together. I think it’s so beautiful that the story comes full circle. It opens with Sweet Charity, and it ends with Sweet Charity. I think that was just a masterstroke of structure.

Agreed. The structure of the series was so intricate with all the seamless flashbacks. And of course, the music had to follow all these journeys in time.

Oh, my God. There were so many flashbacks. It got to the point where I had to have all these charts next to me to keep track of the timelines. Within one episode, we’re bouncing all over the place time-wise, and let’s say I needed a source cue to be played on the radio over here. It was like,” What the hell year are we in right now?” It was very challenging to keep track of the time we were working in.

Luckily, you’re no stranger to detailed spreadsheets. I remember seeing the one you made for the freeway scene in La La Land, which was several pages long.

You know, I love my spreadsheets. It keeps me sane. This business is very chaotic. It’s full of surprises, and you never know what’s going to happen. I feel like a spreadsheet gives me this great sense of accomplishment and the illusion that I’m in control of what I’m working with.

Speaking of La La Land, you extended beyond the traditional duties of a music supervisor while working on Damian Chazelle’s Oscar-winning musical feature film. Because Fosse/Verdon is incredibly choreography dense and showcases many complex musical numbers, what new challenges did this present for you? Which specific sequences required the most detailed attention to perfect?

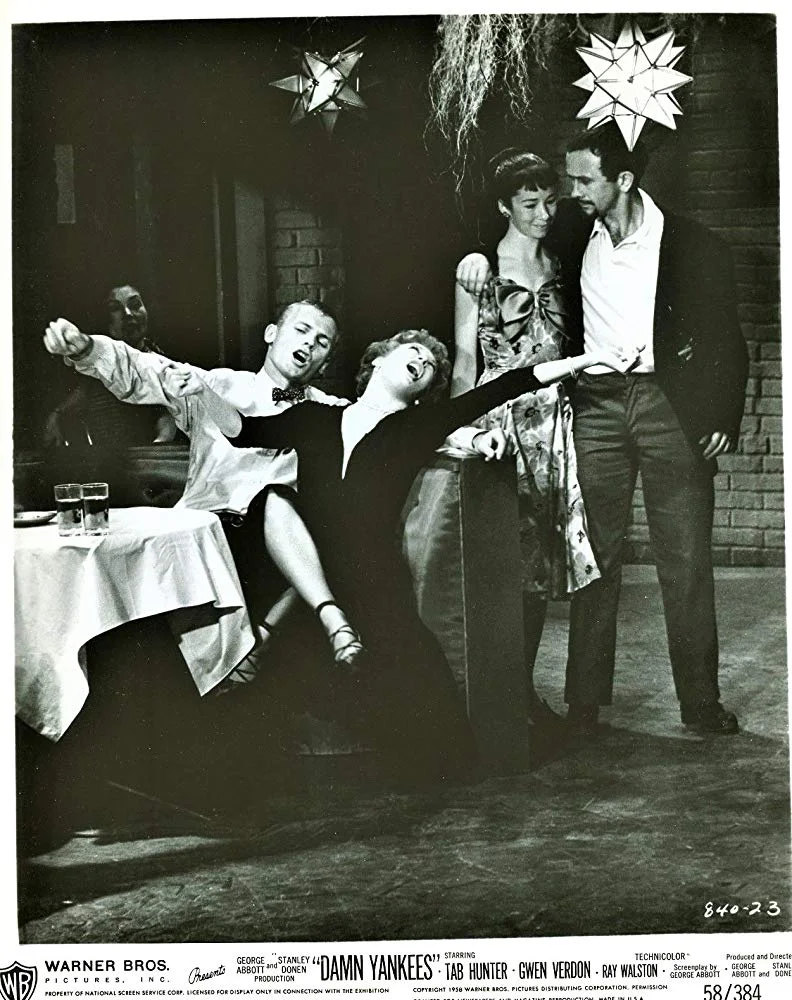

For La La Land, the challenge there was that we were starting from scratch. Damian [Chazelle, director of La La Land] had a vision, and there was nothing but blue sky in creating things. Here, we were tasked with faithfully replicating some very iconic cinema moments, so the challenge was to make it authentic and get it right. For some of these performances from Cabaret, or the Damn Yankees material, we went into the archives and dug out the original orchestrations so that we could match them. We luckily had this orchestrator named Larry Blank, who was just a treasure, and he was around during the day. He worked with Bob [Fosse], and he knows where all the bones are buried. He was such a great resource because he could look at an orchestration, and say, “Oh, by the way, even though it says this on the orchestration, that’s not actually what they played because this tuba player was sick that day.” I’m not exaggerating; it was that detailed.

Throughout Fosse/Verdon, every aspect is so historically accurate, down to whatever briefcase Bob happened to be carrying during that period and so on. We had to do the same with the music. The trick was replicating these musical numbers on a television budget and a television schedule. I was blessed to have Alex [Lacamoire], a really great music team, and of course, the people actually in the show are fantastic. We have some of the best singers in New York, who committed to singing on “Big Spender” and these other numbers.

I would say that the budget and schedule were huge challenges for this production because unlike a film where you have so much time to experiment and get it right, we had to keep chugging along. Because one episode then falls on top of another one, then falls on top of another. So, at any given time, you’re working on five or six episodes at once, and your brain explodes. It really was an eight-hour film and some change, chopped up into eight weeks of television.

Can you describe your phase of research to master the music of Fosse and Verdon’s golden era? Were there any unforeseen obstacles you encountered?

Because I knew I was about to get the job, I started taking a lot of notes while I read [Sam Wasson’s Fosse] because the book went into some detail about what Bob and Gwen might have been listening to in their personal lives, but not much. As soon as the project landed at my feet, the first thing I did was start compiling a playlist. It had every song that had ever appeared in any and every Bob Fosse production. There were a couple of stage shows like Dancin’ and Big Deal that were sort of revues. There weren’t any narrative songs, but there were songs like “I Wanna Be a Dancin’ Man”, and a lot of patriotic songs. It was a vast list of things that were part of his repertoire — that was really my go-to.

Anytime I needed source music material for the show, I wanted to make sure every song was somehow connected to Bob and Gwen, and their story. I would consult with Andy Blankenbuehler, the choreographer for the first few episodes, or Susan Misner in the latter episodes, and we would use those lists as a resource to pull from.

There were some songs I already knew really well because of course, “Big Spender” and “Who’s Got The Pain” are numbers that are in the fabric of culture now, but there were other songs like “Heart” from Damn Yankees that I didn’t know very well, or “Where Am I Going” from Sweet Charity, which had fallen off my radar. Some of the songs we pulled out of the ether and brought them back into the spotlight, so I was very happy to have done so.

We were also fortunate enough to have Nicole Fosse, Bob and Gwen’s daughter, as one of our producers. She would be around on set, so I would just look at her and say, “Hey, in the script, in 1970 whatever, you’re listening to a record, what would you have been listening to?” That was such a great asset. She looked at me, and was like, “I’m afraid to tell you. Can’t we pretend I listened to something cooler?” I just laughed.

There were many times where there wasn’t anything in Bob’s existing repertoire that would fit the moment. I spent a lot of time researching what might have been on the radio at the time, looking for songs that might have intersected with their lives and been a part of their social circle. It was an interesting process because there were certain times we might find a song and think it worked great [for the scene], but then I would dig deeper and be like “Ooh, okay. This part of the episode takes place in August, and the film it’s from came out in October of that year. We can’t use it.”

Sometimes, it’s frustrating when you’re watching a film or television show, and a song comes on the radio that maybe wasn’t released until many years later. That’s the sort of thing that drives me nuts. I mean, unless that’s the point. I think about Marie Antoinette, the Sofia Coppola film. It’s one of my favorite movies, and I loved the use of eighties music in it because it’s anachronistic and I just think it’s brilliant. So, if the music being out of the period is a statement, then yes, it works, but if it’s an accident, not so much.

In the fourth episode “Glory”, there’s a dramatic montage when Bob is contemplating suicide, stepping out on the ledge of his hotel room window. Can you tell us a bit more about how this musical moment was conceived?

Yes, hat’s off to the genius of Alex Lacamoire. Every piece of music in the entire episode is from Pippin. It was a challenge to get approval because everything had to go through Stephen Schwartz himself, and that took a while. There were certain montages set to a sort of punk version of “Simple Joys”, so at the end, as Bob starts to spiral into slight madness, the creative team behind the show really wanted a more musical treatment for it. It was not unlike the end of “All That Jazz” where the people from his life sing various Tin Pan Alley classics to him.

Because we only wanted to pull songs from Pippin, we narrowed it down to the ones that felt appropriate to the moment, and then Alex just got to work on creating this crazy medley of songs. There are a couple of songs that just in there for maybe a few bars, but you hear it’s tiny bit of magic, and then there are some songs that are really prominent like “I Guess I’ll Miss The Man,” which is the final piece.

When our show went big, brash, out there, and crazy, those were my favorite moments, like that Pippin sequence there, and then in episode three, where Bob was trying to edit Cabaret and gets sucked down the hole of the editing room. It’s spinning backward, then we put another song from Cabaret on top of it and turned it around. The first two episodes are somewhat conventional, so to speak. And then at the beginning of episode three, secretaries come out and start dancing in a fantasy sequence, and then he gets sucked down a hallway. Watching that, I was like, “Okay, the wheels are off. We can go anywhere and do anything from here forward. How cool is this?” That’s what’s so great about television. You have eight hours to work with, so you can go nuts sometimes.

Digging deeper into the musical numbers from the series premiere “Life is a Cabaret”, can you elaborate on your experiences overseeing the re-recording processes of essential tracks like “Big Spender” from Sweet Charity, “Mein Herr,” and “Cabaret”?

The first step is obviously to get the rights. So, as soon as the scripts were landing, or we were even having conversations, I would start clearing songs because we need a lot of lead time — to get permission, and to start the recording process in order to finish everything in time for the shoot. That just doesn’t happen overnight, so I had to get a jump on things quickly. When it came time to record, my job was to work with Alex [Lacamoire] to find the appropriate singers, and work with Larry [Blank] to get the orchestrations in place.

Then a lot of times, these orchestrations were so huge, using forty or fifty players, whatever it was, and we couldn’t afford that. We had to get creative and find a way to trim it down to an acceptable number for our friends at Fox that were approving budgets. You know, we could live without maybe a couple of extra horns here and there, but the real challenge was scheduling. While we were in pre-records for a certain episode, we were on set shooting another episode, and then we would be in post-production editing yet another episode. There were times when Alex and I were looking at each other like, “Oh my God, we can’t be in three places at once. You go there, and I go there.” It was a juggling act to the extreme, and that was the most significant challenge of the show.

Your dedication really shows. In general, the horns were just incredible. It sounded as if they were practically jumping out of the speakers on “Big Spender”.

Oh, yes! We had this guy, Derek Lee as our mixer, who’s just brilliant. It’s so interesting that you specifically pointed out the horns because we actually decided to go back and re-do them because they weren’t quite good enough the first time around. We recorded “Big Spender” early on because it was for the first episode. Back then, we had the luxury of being able to record in isolation before we also had to be on set. But then after that, everything collided. And once we hit post-production and we started listening to them more closely, we were like, “Ah, the horns just don’t sound gritty enough or interesting enough.” The magic was missing. Alex [Lacamoire] would always just call me ‘The Budget Police’ because he had to look at me and say, “Gizicki, I want to re-record the horns. Can I do that?” and my job was to make that work.

And for this kind of project, you can’t slap on short trumpet runs from a sample library. The horns have to be real.

Exactly. It’s like, “Okay, I’ve got to book a very large studio and put a bunch of people in there.” And there goes all my money. [laughs]

Considering that the bulk of your supervision work resides in film, what were the creative advantages you attained by taking the audience on this ambitious, logistically daring musical journey over eight episodes? Which sequences and syncs were your personal highlights?

Oh boy. I love the opening of episode one with the performance of “Big Spender” because it’s such an iconic film moment. Every team on the production was on their game — Sam [Rockwell as Bob Fosse] and Michelle [Williams as Gwen Verdon], the women that played the dancers, the costumes, the sets, lighting, et cetera. Everything popped. Initially, that sequence and the opening prologue was maybe ten minutes long. As scripted “Big Spender” was only at the very, very end, like when you see them press play on the playback machine, and then it goes into the number. But then, Alex [Lacamoire] and I were watching, and we realized that the whole thing needed to be scored to “Big Spender.”

I think Alex just did such a beautiful job of scoring “Big Spender” to picture and creating something unique to our show from the existing material. We also wanted most of the scene itself to build, putting layer upon layer upon layer to finally become “Big Spender” at the end. I love that, and it’s still one of my favorite moments.

There’s a great Peggy Lee song, “Show Me The Way To Get Out of This World” in episode two. It was just a really great needle drop. That was one of the moments where you’re just digging through songs from a certain era, most of which you know, but it’s always fun to move past the obvious ones. Right underneath the hits are the second or third songs from an artist’s record that maybe you never heard or don’t remember — that song I just found with the help of the publisher that represents it. I was like, “Oh my God, this song is so great.” and it quickly became a favorite of everybody on the production, so that song, I’m just very proud of.

I have to say that every musical number just makes me so happy. Michelle [Williams] singing “Nowadays” at the piano was so simple. You’d never know it took us a whole day to do it, but the whole show was just so bright. It’s hard to pick a favorite baby, I guess is what I’m saying.

You are presently supervising the film adaptation of In The Heights, which is set for release next summer. Reunited once again with Alex Lacamoire, is there anything you can share about how the music from the original production will be presented?

I can’t share too much yet because it’s scheduled for release next June. Just know, anyone out there that’s a huge fan of the source material, I feel like we’ve done it justice. Lin Manuel-Miranda was with us every step of the way to to make sure we were doing it right. Jon Chu was a brilliant director. He was born to make musicals, so people’s eyeballs are going to pop out of their head when they see this. Some people are already familiar with the original Broadway cast recording, which is phenomenal, but there are limitations in that context. You’re working with a limited sized band, and Broadway show albums are recorded really quickly, like in a span of a day. On this film, we are blessed with time, and we’ve brought in some of the world’s best Latin players. The music just absolutely sizzles, and there are some really great salsa numbers. I think it’s going to be something really, really exciting.

I can’t wait to see Jon M. Chu’s take on In The Heights after doing the Step Up films, Now You See Me 2, and of course Crazy Rich Asians.

That’s actually how Jon and I met. I worked on the on-camera performances for Crazy Rich Asians. We kept in touch, and here I am, the luckiest guy in the world. This career has just given me so many blessings.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Steven Gizicki and Impact24 PR.