Patrick Warren

Patrick Warren is an illuminated composer, producer, and arranger of high merit, continually recognized for his remarkable ability to traverse musical styles. A consummate master of the Chamberlin and a first call multi-instrumentalist, Patrick’s polished musical prowess has attracted collaborations with Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits, Common, Stevie Nicks, Bob Dylan, Chris Cornell, Fiona Apple, Red Hot Chili Peppers, John Legend, Tracy Chapman, Lana Del Rey, and the list of luminaries goes on. In the sphere of music for film and television, Patrick serves as the lead composer for Lena Waithe’s The Chi and has contributed to the sonic statements of True Detective, Fifty Shades of Grey, Crazy Heart, Across The Universe, Boogie Nights, Love, The Great Gatsby, Superfly, and Knocked Up. In our thought provoking exchange, Patrick speaks on the iconic bluesmen that inform his expressive score for The Chi and the qualities he seeks in his collaborators to achieve musical alchemy.

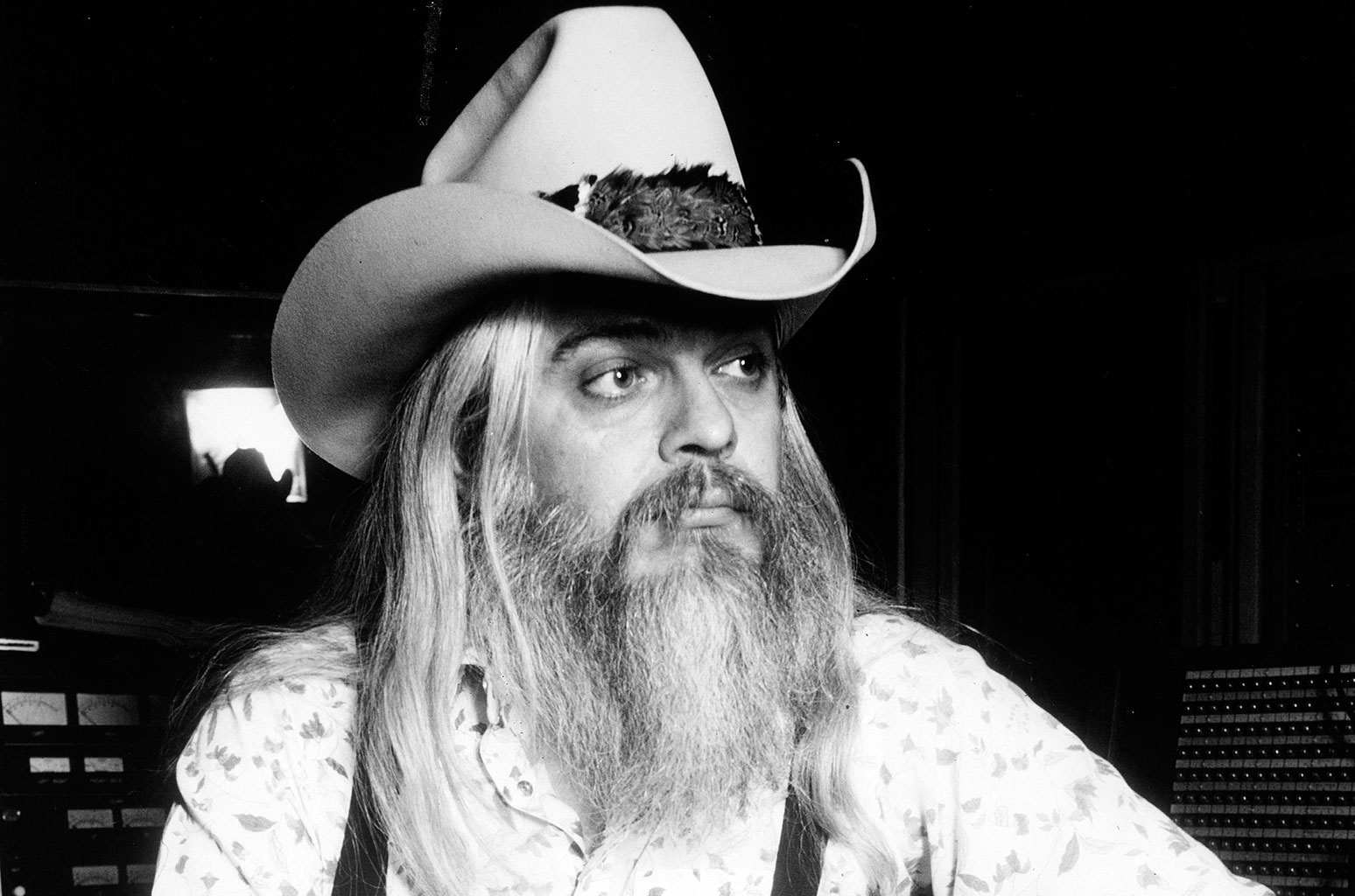

Courtesy of Subject

I read that you are originally from Santa Barbara. Growing up, did you engage in any formal training? How did you cultivate your virtuosic abilities as a pianist and learn the arts of production and arranging?

I was born in Santa Barbara but grew up in L.A. I was given piano lessons at the age of 5 but didn’t take it seriously until about age twelve when I heard Leon Russell on records and thought, “Maybe if I practice enough?”. So I bought an old Wurlitzer electric piano and learned every Ian McLagan and Leon Russell lick I could find. I would drag that piano from house to house, and I’m sure I drove my friends nuts.

After high school, I ended up at Cal Arts as a piano major and studied with the late Leonid Hambro. I quickly became interested in composition and world music. Much of what the students were doing was highly experimental, and I felt like I was at the forefront of something new and important. I also started playing in rock bands around that time and found myself trying every way possible to make keyboards not sound like keyboards, but like orchestras, or guitars, or percussion. Those were the days just before samplers were coming of age. That’s when I discovered the Chamberlin and my world changed!

For those who don’t know, the Chamberlin is an electro-mechanical keyboard created by Wisconsin inventor, Harry Chamberlin. The first iteration was unveiled in 1949; it’s a predecessor of the Mellotron. You are recognized as one of the leading experts of this instrument. How were you initially introduced to the Chamberlin?

I had heard of the Chamberlin in the ’70s, but it was always a kind of far-away dream. I thought you had to be someone famous to even look at one! Somewhere in the mid-’80s, I auditioned to be in a new band with Michael Penn. I somehow passed the audition. I say somehow as I had absolutely no keyboards at the time other than a broken combo organ. During the first rehearsals, I noticed Michael owned a Chamberlin, which was sort of enshrined on a shelf like a Buddhist altar. It was sort of understood that the instrument was not to be played. After some coaxing, and being stuck for ideas on a song we were working on, we brought it down and fired it up. This was the orchestra in a box I’d been searching for!

I had an immediate affinity for the instrument and went out and bought four more over the next few years. Each Chamberlin could hold eight different sounds (instruments), such as cello, violins, woodwinds, and pedal steel guitars. I got to know the inventor, Harry, who lived in Upland, California, about an hour from me. He would make me new tapes, and I eventually ended up buying the masters to his creation after he passed away. The beauty of the instrument is that you can’t really play it like a keyboard. You have to learn to think like the player of whatever instrument tape you have up. To breathe like a trumpet player, or not make leaps on a keyboard that a real cello player could not do. It’s a common mistake I still hear today with new orchestrators doing mockups on a keyboard and playing parts that are impossible on the actual instrument they’re emulating. The Chamberlin was the beginning of my love of orchestral instruments and sounds.

Over the course of your career, you’ve had a hand in the creation of original music for popular films including Boogie Nights, Crazy Heart, Fifty Shades of Grey, Knocked Up, The Great Gatsby, and Across The Universe. Was it an intentional decision to turn your talents to scoring, or was it a natural progression that eventuated from your other professional activities?

I think it was a natural progression from my approach to keyboards. I’ve always treated my parts as an arrangement on some level — always trying to shine a light on the beauty of the song and lyric. I had the good fortune to work with some of the best songwriters of my generation, and a great song and lyric are not unlike a short movie or scene. In fact, in the early days of film scoring, you were just given the written scene and frame number count, and from there, you wrote the score. I was a bit intimidated at first, so I took some extension classes at UCLA and one of the brilliant instructors there, Robert Drasnin said to me, “It’s not rocket science!” We’d be given a scene to write for, and they said, “You have four cellos, four violins, one clarinet, and one flute; write for those instruments and make it work!” We would also study all the instruments separately and learn their strengths and weaknesses. The following week, we would hear our cues played live, and while there were always a few trainwrecks, the experience was fantastic. In addition to all the skills he taught the students, he gave me great courage to compose for film.

The Chi explores the hard realities of life in the South Side of Chicago from the perspective of different generations of African American men. The show presents a culturally vibrant community racked by senseless violence and unexpected traumas. In your opinion, what are the core messages we can learn from this impactful narrative?

It’s my aim to direct the audience’s attention to the humanity of the multiple themes throughout the series. While there’s plenty of inhumanity as well, there’s a story behind how a person might become that way. The core message of the show is different for each person watching. It’s always the reality of living day-to-day in this neighborhood — the hopes, dreams, failures, and heart of the characters — that I like to bring to light with my score. Even the evil characters have a view of themselves that may be different than the actions their taking. It’s interesting to musically get in their head and imagine their own personal soundtrack, rather than playing to the obvious crimes they are perpetrating. On the other side of the street, the people living on the south side have a fierce resilience and big heart that ties them together.

I understand that your previous collaborations with Chicago hip-hop legend and executive producer of The Chi, Common, on Academy Award-winning song, “Glory” from Selma and his album, Black America Again, positioned you to compose for the series. Can you elaborate on how this opportunity came to pass and the conversations that took place to establish the musical vocabulary?

I think my work on Black America Again sparked the idea of me scoring the series. On that record, Common gave me complete artistic freedom to write arrangements against his songs. Inspired by the lyrics and music, I wrote the arrangements differently from anything I had before: harmonically outside the lines and also sort of non-linear and dancing around the lyrics with a sort of modular approach. I think that record found its way into the DNA of my approach to writing for the show. Right after that record, Common called me and asked if I would like to score the series. He said he wanted the score to be something different since there would be plenty of hip-hop source music. I knew what he was envisioning and got right to work!

What is your personal connection to the rich and varied musical traditions hailing from Chicago? Who were the primary influences that formed the basis of your musical direction for The Chi?

For me, it’s the blues artists that I’ve been listening to most of my life: not just Muddy and Willie Dixon, but the players in and around all those camps. You could write a novel around one Little Walter harmonica solo. I’d play them over and over and try to spread the gospel to anyone who I could get to sit still and listen. I would study Pinetop Perkins licks and listen to Sonny Boy Williamson for hours and try to explain to my friends, “That’s not a harmonica overdub! He’s singing and playing at the same time!” From all these artists I’d say their use of space is the primary influence on my writing. A simple Willie Dixon bass line sounds enormous.

I find that small ensembles and a minimalist approach can often be far more compelling than large ensembles. You can’t turn your ears or eyes away when there’s just one instrument playing. You feel and experience the part in your bones. It makes a huge statement. Also working with Karriem Riggins, Common’s producer and co-writer, has a big influence on what I’m doing on The Chi. Karriem is a deep musician, DJ, producer, and writer. He’s a brilliant jazz drummer and hip-hop beat maker. We toured together with Diana Krall and Karriem would spin music all night on the long bus rides. He turned me on to so much music I’d never heard. His approach to beat making is a guiding light for me.

What have been the rewards and challenges of creating a seamless musical identity that embraces a colorful mosaic of licensed material curated by Barry Cole? Referring to season two, how is the sound of the show developing and expanding?

Barry Cole is brilliant and truly one of the hardest working guys I’ve ever met in that field! He also happens to have one of the calmest demeanors of anyone I know, especially considering the time crunch and pressures of the show. The rewards of working with Barry come when the show or episode is complete, and we take a breath and see all the parts become a whole. Sometimes our collaboration will be something simple like a dinner or bar scene. Rather than break the bank on a Muddy or Miles song, I’ll put together an ensemble here in L.A. and sketch out some melodies and let the musicians have their way with it. L.A. is super rich in brilliant players for any genre you might need.

On the other side, it’s always a fun challenge coming out of a source cue and tying it to score. At times, I’ll be asked to put score on top of source and the challenge, of course, is to be seamless and stealthy, so the viewer is unaware you’re there, but nonetheless, you’ve directed their attention to something they were not looking at. In season 2 of The Chi, we’re deeper invested in the lives of these wonderful characters. The cinematography is also richer and deeper in depth and color. This allows for deeper musical colors and melody.

For the past three seasons, you have participated in crafting the musical atmosphere of the remarkable crime anthology series, True Detective with T-Bone Burnett at the helm. The debut season followed two Louisiana detectives tracking down a serial killer over a 17-year stretch, the second investigated a chain of crimes thought to be linked to the murder of a corrupt politician, and the latest third season delves into a macabre crime involving two missing children in the Ozarks. Can you elaborate on the connective threads and motifs that appear across all three scores? What is the ethos at the heart of this collaboration and how much emotional guidance did you all consciously put forth?

I mainly worked on season one and two, although I’m told some of the music I wrote appears in season three. There was definitely a difference in vibe and approach between season one and two. Season one had this great dark bayou/voodoo vibe that was wonderful to write to. Every time you think you’ve got the most evil guy, he’s just another layer in the puzzle of unfolding evil.

T Bone Burnett is absolutely brilliant, and his insightful approach to score and music supervision is an inspiring thing to behold. I’ve worked with T Bone on and off for over 20 years, making records and more recently scoring for picture. He sees the big picture and steers the massive ship with one foot on the wheel and a cocktail in-hand. He makes it look effortless, but it’s not. For the first season, I found myself, along with Keefus Ciancia, leaning toward sounds that I felt would emanate from the land: old Instruments like rusty shaker bells or a very old Dulcitone (a kind of crude bass celesta), wheezy pump organs against a cello, things like that. I wanted every instrument to sound rusty like it was found in a swamp or behind a shed and left out in the rain.

In season two, which takes place around L.A., I think I had novels like The Black Dahlia and In Cold Blood rattling around in my brain as I approached it. There was room for a slightly more noir soundscape. In all three seasons, I think it’s a minimalist approach that ties it together — making a huge statement with the space in between the notes. T Bone is the master of that.

In studios and on stages, you’ve contributed to the artistic work of a vast and eclectic array of musical luminaries including Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, Fiona Apple, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Bruce Springsteen, John Legend, Chris Isaak, Ray LaMontagne, and Lana Del Rey. To what do you credit your versatility and ability to shape shift? What would you specify as some of the milestones you’ve achieved in your career thus far?

I think it’s a simple matter of listening. Being able to step outside yourself and really listen to the heart of a song. If you can do that, you’ll find the parts and arrangements almost play themselves. It’s a hard thing to teach. You have to find the essence of the song and then kind of jump in it! I find musicians either have it, or they don’t.

Recently, I worked on a Jacques Brel tribute record with producer Larry Klein. We recorded much of the music in L.A. and Larry recorded various French artists singing in Paris. When it came time to do some arrangements on a few songs, Larry sent me the French translation of the lyrics/poetry of each song. He knew how important it was for me to understand the lyrics before I started writing anything. Every song has a kind of heart and soul you have to embrace and chase after when you’re playing in a band or recording a record.

Working with Tom Waits was definitely a milestone in my life. He’s been a hero of mine since I first heard his music and to get to work with him on tour and in his studio was something that lives with me still. When I think of milestones, I also think of long relationships I’ve had with artists and producers. Joe Henry is one of those people. I can’t tell you how many records I’ve made with Joe, either his own records or with Joe in the producer’s chair for other artists. The freedom and trust he’s given me on records have helped shape my own confidence in what I’m doing, and I’m incredibly thankful and proud of every record I’ve made with him.

Working with John Legend and Common has likewise opened up a new and wonderful chapter in my life. They are always charting new ground ahead of everyone else and are fearless artists. I just finished working with Common on a few tracks of his next record. It’s a deeply moving record that I’m excited for the world to hear!

As someone who has continually demonstrated the ability to work well with others and produce an impactful final product, what are the components of a synergistic and harmonious collaboration? What are the qualities and skills you value most in those you make music with?

I feel there’s a sort of synergistic love and energy among all the musicians I work with. We all want the same thing, and it’s not for our parts to be cool or dope, but for the song to shine, for the artist to realize the dreams of what their songs could be. It can be so intuitive and harmonious that little or nothing is said during the recording of the music, the main points of discussion being what wine to open on any given night. The ability to read others and know what they’re looking for is more important than your immediate playing skill level (not that you shouldn’t know your instruments).

Also, you have to be somewhat fearless when you’re making music. If you have an idea for a vibe or a part on a song, you have to take that leap and throw caution to the wind. You also need to have a sense of humor. It might seem strange, but for me, it’s a highly valued commodity. A serious approach to music will get you in trouble quick. A fearless, lighthearted approach coupled with a sense of humor and skill is a killer combination and will turn out some of the most deeply moving music you can imagine. Those are the artists and musicians I’m drawn to work with time and time again.

Interviewer | Ruby Gartenberg

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Patrick Warren and Impact24 PR.