Patrick Doyle

Patrick Doyle is the iconic Academy Award, Golden Globe, and BAFTA nominated composer who has enchanted audiences with his opulent and diverse musical stylings for stage and screen over three decades. Patrick’s regal elan, unforgettable melodic sensibilities, and flair for the dramatic have positioned him to serve as the musical storyteller for critically acclaimed films including Gosford Park, Thor, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Murder On The Orient Express, Brave, Cinderella, Sense and Sensibility, Bridget Jones’ Diary, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, Carlito’s Way, Indochine, Great Expectations, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Hamlet, Donnie Brasco, A Little Princess, and As You Like It. In our inspiring conversation, Patrick takes us on a trip down memory lane and delves into his career long artistic immersion in the work of William Shakespeare with a focus on All Is True, his most recent collaboration with Kenneth Branagh.

Courtesy of Subject

I understand that you engaged in a course of study at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music. Can you elaborate on the genesis of your artistry and your trajectory through the world of classical music? Who were the artists and guiding forces that influenced your taste?

Well, I’ve always loved every genre of music. At the age of eighteen, I enrolled as a junior student at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, and I was then a full-time undergraduate for the next three years. I studied singing, piano, tuba, harmony, and counterpoint. I was always very interested in drama and saw virtually every play that the drama students performed at the academy.

My influences throughout my life in music are many, for example, Mozart, Verdi — I’m very much drawn to dramatic music. I love Beethoven, of course. He was a great dramatic composer in his programmatic symphonies and opera. I’m a big fan of Prokofiev and Bartok and contemporary music. I have a very eclectic taste in music. I admire Henry Purcell, the English composer, who composed “Dido and Aeneas” among many other great works.

I’m also an avid reader. I’m a lover of Scottish poetry, especially the Scottish makars from the 14th and 15th centuries. I recently composed a piece for choir and orchestra called “Sweit Rois of Vertew," which is a setting of a poem by William Dunbar. He was a contemporary of Chaucer [Geoffrey, best known as the “Father of English literature,” author of The Canterbury Tales]. These Scots poems have been sadly neglected for centuries, but now there is a wonderful renaissance, and I’m very proud to be a part of it.

Absolutely! In the last few years, we’ve witnessed a resurgence of film music being performed in live contexts.

It’s been terrific to see the popularity of film music concerts increase exponentially since I began composing for film over thirty years ago. It’s absolutely wonderful, and I’m very lucky because I have a body of work that is regularly performed in concerts all over the world. There are some dates coming up soon. My son, Patrick Neil, and I have spent the last two or three years archiving my music and preparing it for concert. Fortunately, the film music I compose first and foremost serves the picture but is also traditionally scored and therefore fairly easily adaptable for the concert stage. I had embarked on this process before this sudden surge in popularity, so I somehow subconsciously anticipated this. I’m delighted it has come to fruition for all film composers. It’s a great art form, so I am very thrilled to be a part of it.

The first film you ever scored was Henry V in 1989, which also marked the beginning of your decorated collaboration with actor and director, Kenneth Branagh. What were the lessons you learned at the start of your career that remain relevant until today? What are your secrets to maintaining a long term creative partnership?

I suppose the main lesson is to keep working very hard because that film's success, in every department, was because of people's very hard work. Film composition is immensely demanding, and every composer will tell you the same. You have to be able to adapt, or you’ll die. Hard work and passion are essential. It is essential to listen to the filmmakers and work very closely with them. You need to grasp their insights, their needs, their perceptions. It’s really about trust, instinct, and exploring fresh ideas.

My relationship with Kenneth Branagh is very symbiotic. We seem to be in each other’s minds a lot. Over the years, you become far more comfortable with one another. He gives me a lot of space to find my voice and follow my instincts. He’s grown to be very trustful of me. I think his latest film, All is True, is a marvelous work, and time will prove that it is indeed a masterpiece.

Your most recent collaboration, All is True examines the adventures and pitfalls of the great William Shakespeare. What were the initial conversations surrounding the musical direction of the film and what did you hope to achieve with this score?

He [Kenneth Branagh] showed me the Chandos portrait of Shakespeare, which was on the wall in his office. It has Rembrandtian lighting — dark on one side, lit on the other. This painting was his inspiration in terms of how Shakespeare would look because he felt it was the most realistic image of him that exists. He then gave me the script, which I read immediately afterward. The night-time film interiors were lit entirely by candlelight. The daytime shots utilized natural light. It's such a creative concept.

Ben Elton’s script — I loved it, and I was extremely moved by it. The family drama was riveting. After the Globe Theater burns down, Shakespeare returns from London to Stratford. He enters into a domestic situation, which is a very well-oiled machine, and he finds it difficult to adapt to this sort of life after his years of career success in London. There’s a lot of tension. The film is very close to the archival evidence of his last few years. He didn't write another play after the Globe burned down. It’s a fascinating story. The actors speak in modern-day language. Of course, there are Shakespearean quotations recited at times by the actors as part of the story. Because the film uses contemporary language, I decided there should be a contemporary score. It’s not a large orchestra — it needed a chamber orchestra. It features strings, solo piano, and harp, with a touch of period instruments from time to time.

Before I began the score, I asked Ken to suggest a poem that would perhaps give me inspiration for a theme. He suggested Oberon's speech from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, "I Know A Bank,” which is read aloud by the actors in the film. Shakespeare's beautiful poetic rhythms formed a wonderful foundation for a melody, which I used in various forms throughout the picture. Inspiration can come at any time. I remember one day, I was sitting in a restaurant in France, and a local band marched into the restaurant and back out again, and I wrote on a napkin one of the themes for Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire inspired by this moment.

Ken also suggested “Fear No More the Heat O' the Sun" from Cymbeline (also recited in the picture) as another musical inspiration. I composed a song set to those words and, to demonstrate it, I sent the music to my daughter Abigail, and she recorded herself singing it at the end of a very busy day, in her bed on her iPhone! She sent me her vocal, I put it together with the accompaniment, and then I sent the track to Ken – and he loved it. He was very keen to use this for the end titles. I didn’t expect him to actually use her voice; I was merely demonstrating what the sound could be like, but the recording Abi made had a very home-like, natural and calm feel to it, which was ideal for the picture. There was an innocent quality in putting down the melody very simply and quickly. That’s the same quality she recreated in the studio later on.

It's an ongoing working relationship between Ken and myself built upon trust, knowledge, and listening to each other. As he was shooting the film, I was composing music and sending ideas to him. It was like chasing a car, but it was very exciting! It was all filmed in a brief period of time, so it needed to be scored in a short time as well. There’s a lot of piano in the score, which I recorded myself. Ken said at one point, “I think you should own this picture,” so I did everything – conducting, orchestrating, and performing. It was demanding but thrilling.

It sounds like quite the family affair!

Yes! Ken said that Abigail was perfect for the song because he has known her all her life and she is part of the family, which was appropriate for the film.

Over the course of a prodigious career, you have created sophisticated, emotionally impactful music for a broad diversity of feature films, acclaimed theatrical performances, and concert works. To what do you attribute your capacity to traverse numerous styles of music successfully? Where does your aptitude for creative flexibility derive from?

I have no idea where the creative flexibility comes from. Perhaps, it’s because I have a keen interest in all genres of music. I haven’t specifically studied the latest pop trends or the current sounds of dance music, but I cock an ear to it occasionally and certainly enjoy analyzing the construct. Above all, I have a great interest in drama and music, full stop. Before I did Thor, I was perceived as a composer who would thrive on a period costume drama or perhaps a light comedy, not necessarily a large Marvel blockbuster film – although I had written the score to Harry Potter by then, but that’s got a wonderful sweeping and mystical quality — it's not necessarily a big action movie. When Thor came along, I thought I would take a rock and roll approach and fuse it with a symphony orchestra.

Other people told me they were surprised when they heard that that score came from me. It was a very challenging assignment with a lot of input from the studio because the franchise is so strong. This resulted in a lot of changes and notes. I learned very quickly to be less precious as a composer. I was prompted to be very chameleon-like and adaptable. It was a bit like being a part of a huge band. That experience of doing a big tent-pole movie at that time in my career was unexpected but ultimately very good for me.

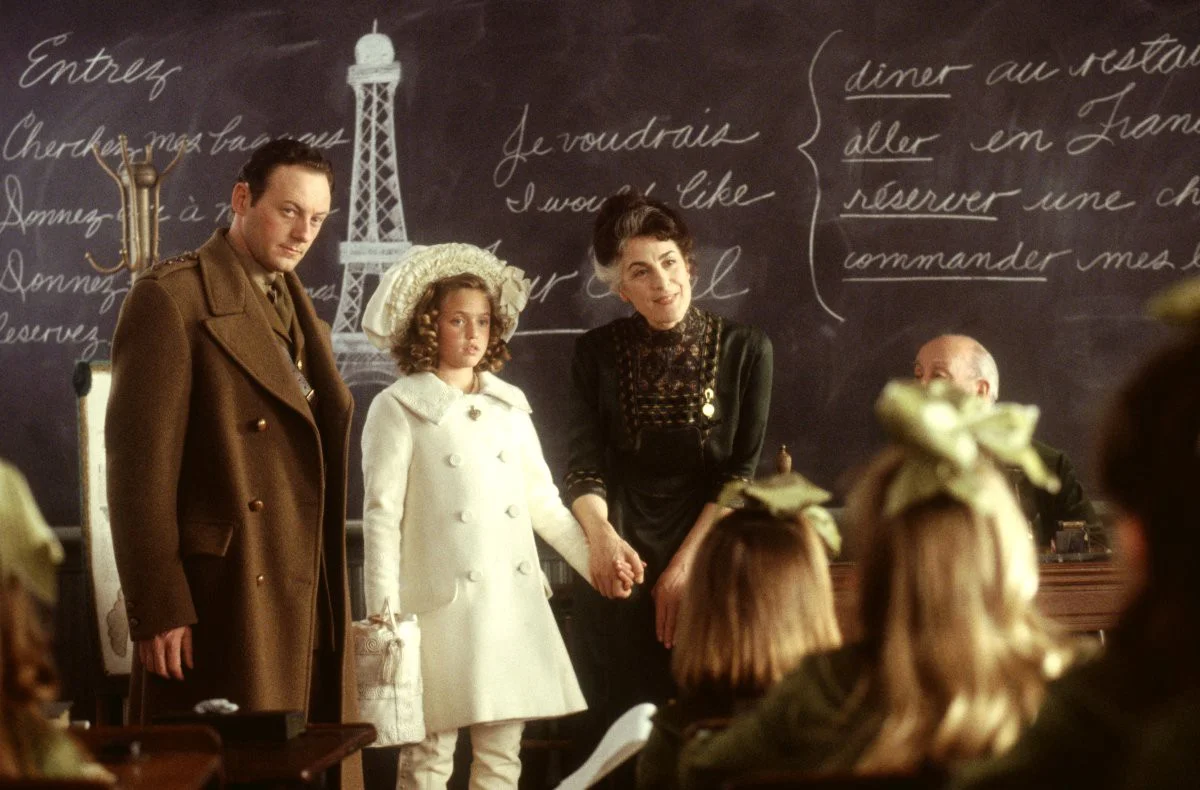

I enjoy a challenge if the subject interests me. I enjoy going with the flow and seeing what comes along. Luckily, I haven’t been typecast or pegged as a genre-specific composer. Thank goodness! I’ve done light comedies, action movies, costume dramas, historical films — projects filled with magic and very serious pictures. I’ve composed, of course, for many Shakespeare adaptations with Ken. I wrote for Sense and Sensibility with Ang Lee. I collaborated with Alfonso Cuáron on Great Expectations and A Little Princess.

It was an extraordinary privilege to work on Gosford Park with the iconic director, Robert Altman. My daughter Abigail sang two songs in the film and co-wrote one of them with myself and the other with Robert when she was only nineteen, and I was really proud of her. I absolutely adored Robert and his wife Kathryn [Reed]. My wife, Lesley, and I became great friends with them both. We had dinner with Kathryn a few months before she died and had the most wonderful, memorable evening. She was a very sassy and amusing lady, and she said, "I always go where the action is." She made us laugh a lot — we loved her. I must say that I’ve been very lucky in my career and have met some wonderful people.

To date, what music are you most proud of?

The score for Henry V — my first film with Ken — means everything to me and my family because it was my first great opportunity. It was Ken’s first picture, the producer’s first picture, my first, and all the actors'. I’m still very good friends with many of the actors in that film, including Derek Jacobi and his partner Richard Clifford, Emma Thompson and her sister Sophie. I’ve been very lucky to work with great directors, talented actors, as well as brilliant people in every department in film.

I've written many concert pieces, and two of them I am very proud of. The first is the “Violin Romance” from As You Like It, which is dedicated to my wife, and I wouldn't be here without her. The second piece is “Corarsik,” composed for my great friend Emma Thompson's birthday and, thirdly, a Scottish Overture composed for the Glasgow Celtic Connections festival.

I was invited to the Prague Shakespeare Festival this year by my great friends Guy Roberts and Jessica Boone, who established the Prague Shakespeare Company almost ten years ago. They invited people from all over the world. It was brilliantly organized, and it was wonderful to meet all the members of these Shakespeare companies. Imagine all these Shakespeare fans, including myself, in one place for a week! Of course, I was as happy as a pig in muck. It was one long party; it was just amazing! They performed a concert of my music, which was the opening night, and they also held a special screening of All is True. Sony Pictures kindly permitted the organizers to screen the film before its release. It was such a special treat for them. The audience was beside themselves, moved to tears. It made me think of all the work with Ken and all the impact it’s made on the lives of so many. I’ve always loved the work of Shakespeare. I adored it in school, but I never thought that I’d end up being so immersed in his work. I’ve been very fortunate.

As you were saying before, it seems like your love of literature and poetry has influenced your work greatly.

Yes, I certainly love poetry and literature. I read every day. I also love factual reading and historical works, for example, biographies. I’m always studying scores and listening to music.

I was asked to be a music consultant for a wonderful novel by an amazing Scottish writer called William Boyd. The book is called Love Is Blind. He came down to my studio one day and was asking me all sorts of questions about music: "Why does this music move me here?" I would say, "Well that's the suspension. And that's a passing note, and that's a leading note. That's a modulation. That's an interrupted cadence." A lot of that musical terminology ended up in William's novel! So far, the feedback from the musical community has been tremendous. His book is a marvelous read. I cannot recommend it enough. It was such a thrill to go to the last page and see a dedication to myself and my son, Patrick [Patrick Neil Doyle], who also helped. I received so many emails, asking “Oh…is that you?”. It was such fun and a pleasant surprise to contribute to William's book, as it was such a diversification from what I normally do.

In 2017, you took on Murder On The Orient Express, a compelling rendering of the classic mystery thriller based on Agatha Christie's 1934 novel. Your score feels like a voyage in itself, pairing dramatic orchestral performances with rich use of instrumentation from far-flung corners of the world. Can you walk us through the palette you assembled and tell us about the musical experiments that took place to establish the tone of the film?

Yes! In advance of doing a film, I always create a template of various sounds. I assembled a conceptual suite inspired by oriental and occidental music and early classical music. I used various indigenous flute sounds and Turkish instruments, including the zither, the cimbalom, the ney flute, and a small amount of duduk. These timbres were chosen to give you a sense of where you are.

For the Orient Express theme, I used an ostinato motif to symbolize the movement of the train, along with rising arpeggios. For the Armstrong theme, I used delicate piano and solo cello. I had also written this song called “Night Train,” which was later used in the film as a piece for solo piano. It featured nice 1940s harmonies and used these sort-of “woo-woo” calls played by a group of saxophones, which sounded like the train horn. There were two ways I created sounds and resonance for the train. That, and the “chugga-chugga-chugga-chugga” of the string ostinato. You can hear this in the piece, "The Orient Express." I mixed the rhythm of the train with the thematic material of "Poirot's Theme". I drew a little bit of inspiration from a theme in Carlito’s Way — the train at the end, the onscreen pianist.

As I mentioned, the song "Night Train" was never used, but the solo piano version called "Poirot's Theme" was used when Poirot comes off the train at the very end. It’s quite jazzy, melancholic, and wistful. Overall, it was a very rich palette of thematic material and melodies, but the music for Poirot, the Orient Express and the Armstrong family were the most prominent motifs in the film.

How was Michelle Pfeiffer convinced to sing for "Never Forget”?

Well, that song came very late in the process. In the last couple of weeks working on the score, Ken said that the Armstrong theme would make a beautiful song. I sent him the melody, and he put words to the first verse. I then composed the rest of the song, sent it back to him, and he completed the lyrics for the last verse and the chorus. After that, he said, “Why don’t we get Michelle Pfeiffer to sing it rather than a pop artist as she is a major character in the film?”. She [Michelle Pfeiffer] agreed, so I flew to San Francisco to help her, and we recorded it all there. She was quite nervous, but so well prepared. I remember she said, “I’m not Rihanna!” and I replied, “We don’t want Rihanna! We want you. Using your voice will make for an organic extension of the score.” She was delightful — a true professional inside and out.

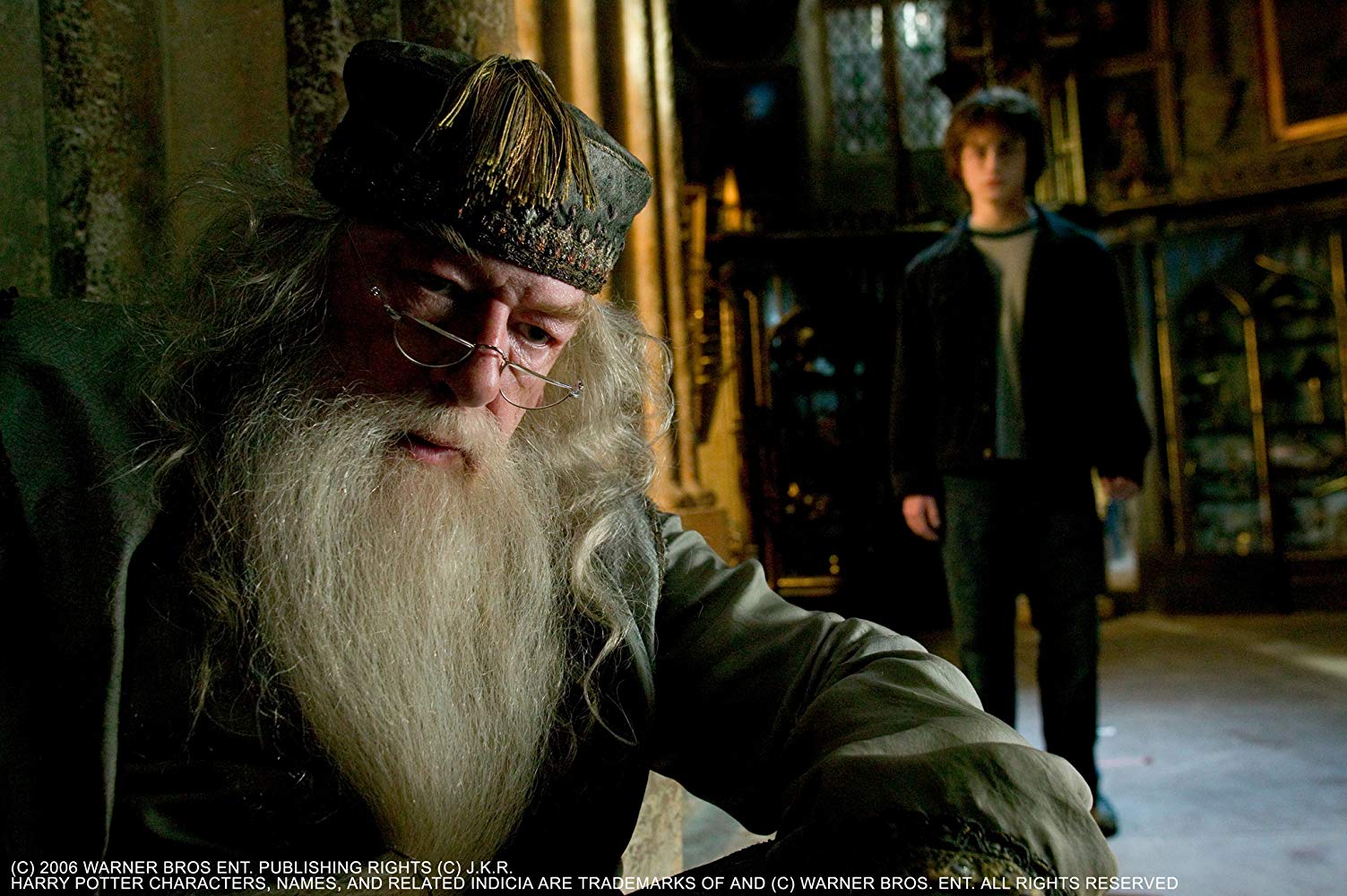

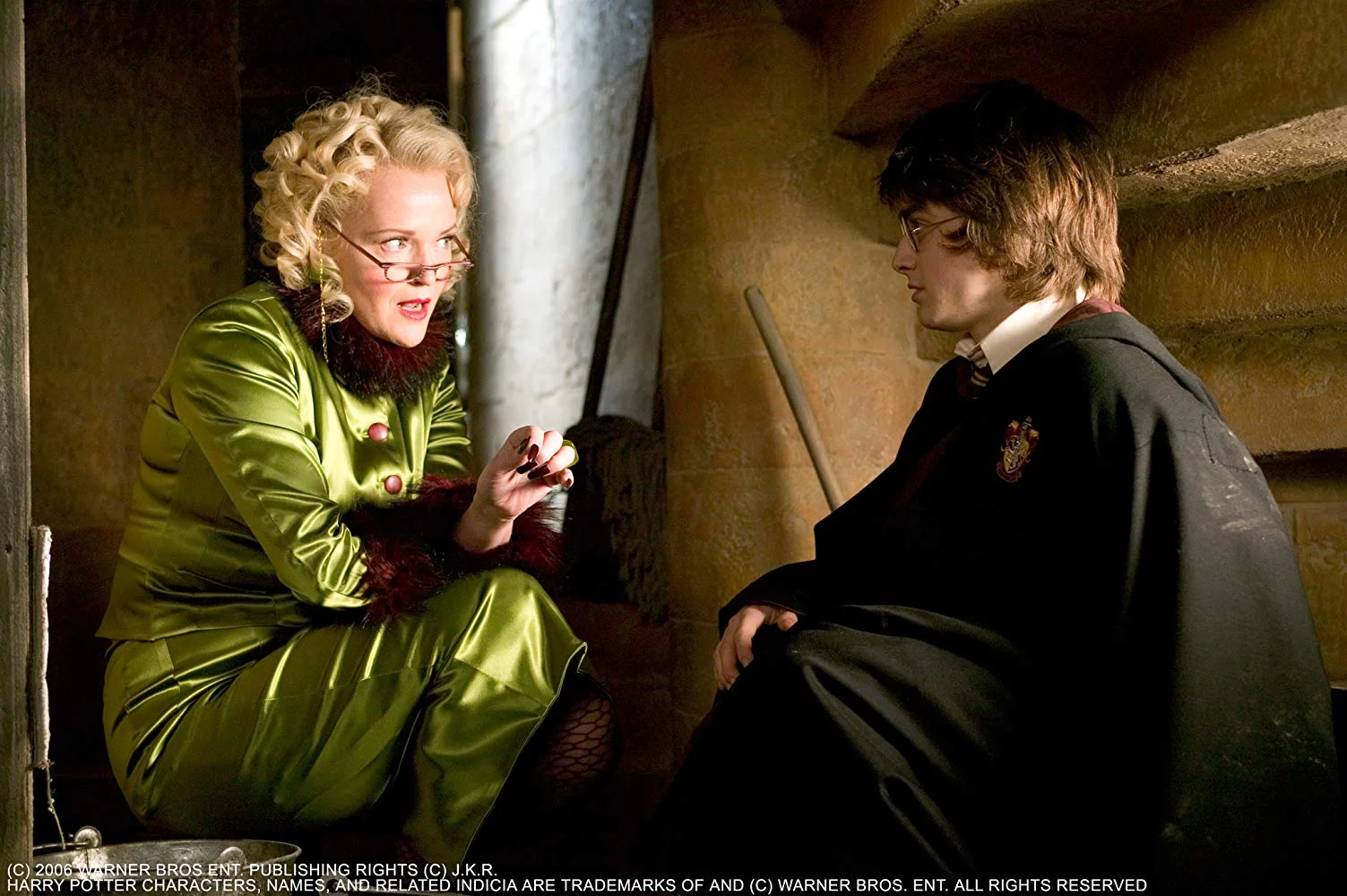

You received the opportunity to score Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, the fourth film in J.K. Rowling's iconic franchise, taking over the duties previously performed by John Williams. What were the challenges of continuing in the line of energy conveyed in the work of your predecessor while prioritizing your own identity?

I was delighted to be asked to do Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. The filmmakers explained this fourth film was quite a different shift in gear in the story from the previous installments. When I read the script, I realized of course that they were correct and that it was a much darker story, and of course Harry Potter and his friends were now teenagers. The Voldemort encounter was far more prevalent and malevolent. Moody was a great character, and of course, there was the love element and the ball. The story, on the whole, is very dark and it was a great opportunity to exploit the symphony orchestra in creating my own voice. It was a great honor to follow in the footsteps of John Williams.

Absolutely, especially a franchise with such a loyal fanbase and incredible cultural relevance.

I'm always astonished when my music's played all over the world, and I'm sure other composers feel the same. I was on a cruise with my family — my relatives, my sisters, and my brothers. We were walking along the corridor of this ocean liner, and I heard my music coming through the speakers. It was so funny to be in the middle of the Mediterranean on a huge cruise ship with my brothers and sisters and hear my music playing — from Sense and Sensibility, and then from Harry Potter. It was extraordinary. As a youngster from a big working-class family, it never ever crossed my mind that I would find myself in such a privileged position. I’m very honored and grateful for it.

What can we anticipate from you next? Can you share anything about your score for Disney's upcoming fantasy adventure film, Artemis Fowl?

I’m busy with Ken for the next two years! We’re doing Death on the Nile and yes, Artemis Fowl. It is a great big action movie — fantasy adventure with a very contemporary sounding score. Without a doubt, it has a strong Celtic feel to it, considering much of the film takes place in Ireland. I haven’t written it yet, so I’m merely imagining. I haven’t had detailed discussions with the filmmakers yet, but I can imagine those qualities. It’s truly an incredible world. I would love to say much more about it, but then I’d spoil it.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Editing | Ruby Gartenberg, Alex Sicular

Extending gratitude to Patrick Doyle, White Bear PR, and Air Edel Music.