Miriam Cutler

Miriam Cutler is the triumphant Emmy nominated composer and relentless activist, commonly regarded as the ‘Queen of Documentary Scoring.’ Uniting her passions for world music traditions and social, political, and environmental advocacy, Miriam has scored a kaleidoscopic array of meaningful and critically acclaimed projects including The Hunting Ground, RBG, Ghosts of Abu Ghraib, A Plastic Ocean, Vito, The Desert of Forbidden Art, Ethel, American Promise, Lost In La Mancha, Thin, The Breast Archives, Love, Gilda, and Dark Money. In her prodigious body of work, Miriam has demonstrated a rare, highly attuned gift for musically addressing scandals, exposés, the personal lives of impactful public figures, as well as critical aspects of history and the human condition. A co-founder of the Alliance for Women Film Composers, Miriam, along with Laura Karpman and Lolita Ritmanis, was honored with the BMI Champion Award for her outstanding leadership in 2018. In our rewarding exchange, Miriam discusses her path to a purpose-driven career in the arts and her experience as a navigator and tastemaker in the ‘post-truth’ era.

Courtesy of Subject

Can you tell us about your entrance to music making and how that progressed into a vocation? What initiated your interest in world music?

I came from a very musical family. My parents were all about business – they didn't consider music to be something one did as, you know, a career. Still, we all played instruments, and it was part of our lives. I played piano, guitar, clarinet, and was fairly adept at any instrument I picked up. In my teens, I discovered and became passionate about international folk dancing. That was my introduction to World Music.

Being a clarinet player, I dove into playing in ethnic bands to accompany folk dancers. That led to my interest in Anthropology and ethnomusicology, which I studied in college and even went to grad school for. I also developed a deep interest in social justice work and left grad school just shortly before I was to finish my Masters. I worked as a Vista volunteer with some public interest lawyers for four years, but during all that time, I was in three bands — a feminist topical band I wrote all the music for called Alice Stone, The Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo, and eventually, my own original band. Playing with such good musicians inspired me to take composition and musicianship classes at SMCC. I wanted to be the best musician I could.

Starting in the mid-1980s, I made the transition from performer-songwriter to writer/producer, because I wanted something more. Now I was making a living — playing in bands, writing, producing and pitching songs, and eventually scoring low budget films, industrials, and circus. I was getting songs into movies, and as the studio technology evolved from analog to digital, I made my project studio much more professional. Although things were going well and I was actually making a living, after about ten years, I began to question my direction. I put my heart and soul into the music but too often the films weren't good. I love making music, but I wanted to serve some higher purpose.

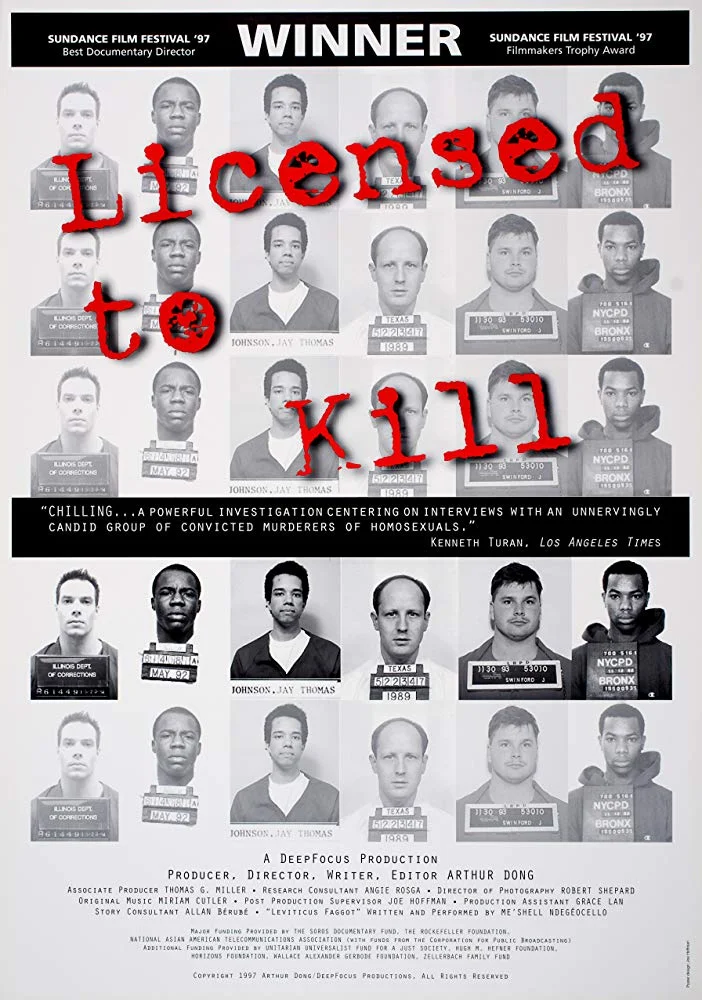

The turning point came in 1997 when I met a filmmaker at one of my screenings, who was making a film called Licensed To Kill. When he told me that he was going into prisons and interviewing men who had murdered gay men to find out why they thought that was ok, I was floored – I had to work on this film. He was a very respected documentary filmmaker, and this was a project I could really be proud to be part of. We went to Sundance, and a whole new world opened up to me. The film won two awards, and I was introduced to this amazing community of passionate documentary filmmakers. I felt like I had finally found what I was looking for.

When you entered the field of film scoring, there were far less female role models to study or emulate, though trailblazers like Shirley Walker, Wendy Carlos, and later, Rachel Portman come to mind. What would you consider to be your breakthrough project and who were some of your earliest supporters?

It's an interesting question, but not quite applicable in my case. It's true that the only woman composers I was aware of in the late 1980s were Shirley Walker and Nan Schwartz. But when I first started, I had no real concept of what a career as a film composer would look like. I just followed my instincts and acted on every opportunity to create music for any project that came my way. I never actually thought of myself as a film composer, just an extended version of a working musician. And I've always been a magnet for work because I see opportunities where others don't so once the ball was rolling, it never stopped. When I discovered my passion for documentary work, I was much more focused. I started meeting more people, and I went to Sundance almost every year. I made it my goal to become part of the documentary community, and I have. It's the kind of work I'm inspired to do, and I've worked on many award-winning documentaries that I am proud of.

I would say that my earliest supporters were documentary filmmakers — Arthur Dong, Kate Amend, Lisa Leeman, Rory Kennedy. I learned so much from each of them, and they, in turn, referred me to other filmmakers. And some of my long-time musicians were incredibly supportive as I transitioned from bandleader/songwriter to music producer/film composer — Ira Ingber, Carl Sealove, Marcy Vaj, Robin Lorenz. And I cannot leave out BMI's Doreen Ringer-Ross who has been with me on this journey from the Songwriters Showcase of the 1970s through my stints as an advisor for the Sundance Doc Composers lab, and who came to some of my earliest screenings at Sundance! She also was instrumental in the formation of our Alliance for Women Film Composers.

In the early years, I found myself waiting for some determining factor that would indicate I was on the right path. Would I ever have any kind of security, respect, higher pay? Working in independent film is very challenging — low budgets, major deadlines, endless workload, having to adapt to constant updated cuts of a film. I was scanning the horizon for my breakthrough project, but after about ten-twelve years, I realized I had actually surpassed my expectations and had been too busy working to notice. I have a steady stream of high-quality projects, a sustainable business model, I work with people I admire and respect, and have been recognized by my peers in the film and music communities.

You are often referred to as the 'Queen of Documentary Scoring.' What is it about the genre that has captivated your attention for so long? What are the crucial considerations one must take into account when preparing to musically support real-life stories that often explore sensitive and sometimes, dangerous topics? Is there an added layer of pressure when the subjects are directly involved in the creative process?

People think it's unusual that my focus is working on documentaries, but I have an affinity for independent filmmakers. I'm both an activist and an artist; I need the combination of social consciousness and music that documentaries provide. The filmmakers inspire me; we share values, and I'm honored to be a collaborator on their important work. There is a deep sense of purpose and commitment by most of them, to tell real stories in a very responsible way, plus I'm always learning something new.

And yes, I feel a huge responsibility to the people in the film and the audience to be true and honest while doing my best to serve the filmmaker's vision for telling the story in an engaging way. Filmmakers and people who participate in docs often make huge sacrifices or put themselves at great risk, so the stakes can be really high. Setting the right tone is really important. If the music doesn't ring true or is out of step and not telling the same story, you may lose the audience's trust and/or distract them from focusing on the content. In a documentary, it's more obvious if music is used in a manipulative or careless way, and this could also create distrust by the audience. It's also very important to never lose focus on the narrative – never let the music seduce me into paying more attention to my musical creation at the expense of the meaning of the sequence.

Documentaries can be seen as an extension of journalism. What areas of interest do you personally consider worthy of exposure or advocacy? To what degree are the projects you take on dictated by your belief system, passions, and convictions?

I often take projects because I want to learn more about a subject. I love a good story. I'm passionate about social justice, the environment, heroic humans, our planet, science, ideas, etc. I want to work with particularly interesting and inspiring filmmakers. I want to fall in love with a film, believe in it, support its cause. Why spend a minute doing anything that goes against my beliefs or causes harm?

You are a long term activist who has participated in countless projects that have brought attention to otherwise unexplored social and political controversies. Do you believe that the documentaries you have contributed to have been effective vehicles to foment change? If so, what have been the most meaningful ways you've seen their impact manifest?

Wow, have you got a week? A Plastic Ocean [directed by Craig Leeson] was a pioneering film about environmental catastrophe taking place in our oceans and has been screened all over the world and is used to organize locally to take action. In just a few years, we are seeing a major shift in the awareness of this problem. One Lucky Elephant [directed by Lisa Leeman] explored the life of a wild-captured African elephant in a circus and the ethics of capturing wild animals to perform tricks for us with the expectation that they will love us the way we love them. This was one of the early docs on the subject, and it contributed a lot towards opening up the conversation about this subject. In fact, over the past nine years since it was released, wild animals performing in circuses has been virtually outlawed, and people have entirely different concepts about zoos and circuses.

Ghosts of Abu Ghraib [directed by Rory Kennedy] was one of the first exposés to publicize the abuses carried out in the name of our government. Dark Money [directed by Kimberly Reed] explored the dire effects of Citizens United on our democracy by covering our elections for three cycles after it passed and helped educate and motivate voters leading into the 2018 election. The Hunting Ground [directed by Kirby Dick] had a huge impact on the problem of sexual assault on college campuses and not only helped bring the conversation out into the open but was utilized by the Obama Administration to help raise awareness during its enactment of new legislation. I've done docs on global child slavery and AIDS that have been shown at the UN to help inform international representatives, a doc on post postpartum psychosis that we hope will educate the public and help prevent unnecessary deaths and misery; eating disorders. RBG [directed by Julie Cohen and Betsy West] brought public awareness about the Supreme Court and the work that has been done by Justice Ginsberg for women's rights during her long career on the Court and at the ACLU. And so many more. I am so proud to be part of all this.

From your perspective, what is the role of documentary cinema in the current mediascape? How have digital distribution and social media revolutionized the potentials for expanded reach and engagement from the public?

Wow — big subject. In these troubled times of garbled news and disinformation campaigns, I believe there is a hunger for trustworthy information that delves deeply into subjects in a reliable way. I think that is contributing to the uptick in interest and production of documentary content. Increased access via internet streaming is making it more accessible to a global audience in an unprecedented way, plus the internet has an insatiable need for content and docs are less expensive to produce.

Betsy West and Julie Cohen's RBG examines the historic career and legacy of the second female United States Supreme Court Justice, Ruth Bader Ginsburg. In your view, what has Ruth Bader Ginsburg accomplished for womankind, and why do you think she continues to be such an icon in modern American life? What were the guiding forces behind the sonic palette you selected to capture the essence of RBG?

Without RBG, my life and career and those of every other modern woman would not be possible. Before her landmark cases with the ACLU, women had fewer rights and were kept dependent on men financially — no credit, no equal pay, no independence. A married woman had to go where her husband moved — it was actually a law. She is a tiny woman of great and gentle power. She is a giant and a genius of the law who works quietly and effectively towards justice. This country is a better place because she has been here. I was very intimidated by the responsibility of representing her musically. But, I quieted my mind and got on with exploring the best way to express her dignity, heart, and soul musically. I knew that she was a great lover of the classics, and since the filmmakers included some of her favorite pieces, I contrasted that with an intimate score meant to reflect her personal story.

Dark Money is an incisive exposé, exploring the influence of untraceable corporate "donations" on the American political system. There is an ominous sense of mystery communicated in this narrative. In your initial conversations with the director, Kimberly Reed, how was the conceptual framework for the musical identity of the film envisioned?

Kim was very clear about what she wanted from the music. The opening was meant to be dramatic in an operatic sense. There was music for the good guys and music for the bad guys. There was music for environmental tragedy, and there was procedural music to help connect the dots and move the viewer through a complex subject. And there was a musical response to the many bizarre plot twists. It was really fun and super exciting to be part of. She wanted to get the audience emotionally invested in the material, even though it's a subject that can make your eyes glaze over. Audiences have really responded well to the film, and it's been utilized by community organizers working all over the country to protect our elections.

Lisa DaPolito's Love, Gilda offers an intimate and compelling portrait of the life and times of American comedienne, Gilda Radner. Why do you think Gilda's spirit and unique sense of humor continue to resonate? What was the most gratifying aspect of executing the musical treatment for this illuminating film?

Gilda was a complex human being with tremendous heart and full of love. Her work will never be stale. Through her comedy, she bared her soul in such an innocent and delightful way. Her legacy continues to resonate and entertain because people can feel her, and we see ourselves and all our foibles through her and can laugh about it. Most of the greatest comedians of our time were also tragic figures with dramatic lives. They were able to tap into their pain and share it with us and provide comfort. Spending time with Gilda Radner while I worked on the film was one of the most wonderful experiences I've had. Once I was able to feel a musical approach, it was a pleasure to let it flow out. Ukulele was the key!

The Hunting Ground reveals the culture of impunity surrounding college campus rapes in the United States, the deplorable treatment of sexual assault victims, and the damaging psychological consequences of coming forward. As a feminist and someone who cares deeply about human rights, what did it mean to you to participate in this groundbreaking project and what factors dictated your musical direction?

I wanted very much to work on this film and pursued it. The film ignited the conversation by bringing this problem way out into the open, making it impossible to ignore and disintegrating the shame that had been silencing survivors for far too long. From the time I started writing the score, the film changed a lot, as the narrative evolved and the filmmakers kept shooting and incorporating footage shot by students. So, I wrote a lot of music that had to be trashed and re-thought, but I was undaunted because I believed so strongly in the work, and knew it would have a huge impact on this problem.

As the film took shape, there were a lot of aspects of the story to be covered by the music — the excitement and promise of starting college, the nightmarish assaults, the re-victimization by college administrations, the violence of the fraternities and privileged elite athletes. Then victims becoming survivors, becoming activists, and organizing all across the country. Very empowering and very exciting. It culminated in the White House! There were also some wonderful songs (thanks to music supervisor Bonnie Greenberg) I had to integrate with and a magnificent anthem by Diane Warren and Lady Gaga (nominated for an Oscar, performed by Lady Gaga, and an appearance by Joe Biden!) So, yes, there was a lot of music and many musical challenges, and somehow, we finished barely in time for our Sundance premiere.

Last year, you, alongside Laura Karpman and Lolita Ritmanis, were honored with the BMI Champion Award for your commitment to supporting female talent in film music through The Alliance of Women Film Composers. Can you elaborate on how conditions have changed since you broke into this industry? What have been the greatest successes of the AWFC to date and what milestones would you like to see realized in the years to come?

As I said earlier, when I first started, I was only aware of Shirley Walker, Nan Schwartz, and later, Rachel Portman and Laura Karpman. We like to think that there's no longer gender stereotypes or a glass ceiling, but statistics don't lie. On the top 250 grossing films of 2018, women comprised 6% of composers. This represents a 3% increase since 2017. [Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film] The statistics tell us that there's still no diversity in terms of who's getting the major opportunities in the film/TV composing field. There's definitely more visible working women composers now, but there's still a lot of work to do on this.

The Alliance has shone a light on the issue and offered remedies. This has coincided with the larger struggle over lack of diversity in our industry. So the good news is that Hollywood is openly grappling with how to respond to public calls for change, and the Alliance and women are part of the conversation.

I think now there are more young women who see themselves as anything they want to be than ever before. They're ready to do it. They're ambitious and undaunted. But even with this new awareness of our actual numbers, women are rarely hired for major films. Still, there is cause for hope. There are definitely more opportunities available than before. This year, Captain Marvel marked the first major global box office hit scored by a woman, and there are more of us making a mark in independent film, on TV and the Internet.

Do you see the irony in speaking truth to power in an era that is commonly referred to as "post-truth"?

Not irony – but rather great tragedy. History happened, and we've already been through this many times. But sadly, here we go again. Truth matters. It is still a shared concept. They try to drown it out with misinformation and outright lies, but facts exist whether they choose to recognize them or not. Weaponizing ignorance and fear leading to unnecessary destruction and despair has been all too common in human history. Truth does not change because someone doesn't accept it – just like science. So we will continue to speak truth, and hopefully, outsmart and defeat this latest wave of self-serving neanderthal liars. In the end, they will be destroyed by the very facts they are trying to eliminate. Let's hope we all aren't.

Interviewer | Ruby Gartenberg

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Miriam Cutler and White Bear PR.