Max Richter

Max Richter is the elegant contemporary classical artist and Emmy nominated composer behind a myriad of esteemed films and television shows including Mary Queen of Scots, Never Look Away, The Leftovers, White Boy Rick, Taboo, Hostiles, My Brilliant Friend, Morgan, Miss Sloane, Womb, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, and Black Mirror. A leader in the post minimalist movement, Max has released eight transcendent albums including Sleep, his ambitious 8 hour concept project, exploring the neuroscience of rest, and Recomposed, an ingenious reimagining of Vivaldi’s iconic The Four Seasons. In our stimulating conversation, Max reveals his fascination with Elizabethan musical traditions that informed his treatment for Mary Queen of Scots and the foundational concepts he devised for the diabolical world of Taboo.

Source: Yulia Mahr

Mary Queen of Scots is a dramatic retelling of the notorious clash between Mary, Queen of Scots and her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I in 1569. What are the challenges of participating in a contemporary project that involves historical recreation?

Well, the different timelines and the connections between them are really what's most challenging about the project, and also what's interesting about it. The two queens were virtually heads of state but were actually in a very circumscribed situation politically. They inhabited a world of men, and they were having to negotiate their way very carefully through male power structures in order to get to what they were trying to achieve, which was very difficult. They were also the only living people who could really understand one another.

They were both solitary women, isolated by their social position and paradoxically, of course, they couldn't really understand one another because they were in this adversarial position. It's a very complicated story, a very interesting story. And of course, in our own time, with all of the kind of inquiry, and soul searching, and questioning what's going on about gender power dynamics in our culture at the moment, it felt very, very sort of relevant and urgent to our own time to get into this story once more.

From a musical standpoint, the obvious challenge is to try and make material which has historical resonance, but without being some clone or copy of Elizabethan music. It's mostly orchestral. There are some solo instruments. There's some choral material, which is fun. I made a choral set of clouds, almost. I did it by using a bunch of different processing in the studio, making these women's voices into something that could feel more like a landscape than people singing.

I got a renaissance choir, people who specialize in singing Elizabethan music, and I wrote a bunch of material for them in the style of Elizabethan music without being a copy of it. I processed that in the tape recorders and the computers to make something which feels a bit more like an ambient space. I wanted the women's voices to always be present in the music. The women's voices are really, for me, the starting point of the score. It's the first and last thing you hear in the film. So, whether it's directly hearing the female singers singing, or whether it's just abstract ambient space made from women's voices, they're always present there.

Considering the rigid specifications of time and place, did you engage in focused study in advance of fashioning your score, or was your process based on intuition and the subliminal?

There were two reasons why I took the film. The first is, I was really interested in the gender politics, and I wanted to work with Josie Rourke, who's a wonderful director. The other reason is that Elizabethan music is kind of my favorite music — I studied it at university conservatory for years. So, for me, it was a wonderful opportunity to reconnect with some of the grammar and technical processes in Elizabethan music — to try and bring those into our own time. It’s a perfect, wonderful gig.

Throughout Mary Queens of Scots, one can hear clear delineations between the thematic material assigned to women versus men. What inspired these contrasting musical identities? Was this a core topic of discussion with the director, Josie Rourke?

We talked about thematic principles, but once I got into the writing, as often happens, the material almost starts to develop a mind of its own. Certain kinds of material grow, and they stick to certain things. It's quite an organic process, but I did want to have a shared theme for the two queens. Even though they're adversaries, they inhabit a very similar world with very similar challenges. That's this quite grand, regal music with a big orchestra playing it. It’s built on a thing called a ground bass, which is an Elizabethan technique, which is similar to a repeating bass line.

And then I wanted some music which was an anti version of that —something in opposition to it. That is the music of the men, which is, again, built on another ground bass — a much simpler, cruder one. It’s like a heavy, blunt instrument. I think the difference between the two is that the music of the queens has an elevating quality — it’s more beautiful — and the music for the guys is like an orchestral death metal.

We are thrilled to hear that Taboo will be returning for a second season. Set in 1814, the series follows a savage who returns to England from Africa to attend his father's funeral and goes after the East India Company with a vengeance. What aspects of this musical landscape require the most attention and care to execute?

Taboo is all about the energy of Tom’s [Hardy, lead actor] character. The story of Taboo is one man against the world. Delaney has an almost magical savagery — some revenge, all these sorts of qualities. Taboo is very, very operatic. Everything is turned up to 11. It's very overwrought; it’s all super intense. The music in Taboo is way over the top. It just throws everything at it all the time. It’s a really wild ride, and it was a wonderful opportunity to go nuts with orchestral music. I really enjoyed it, so we shall see what happens next.

What are the signature musical flourishes that you have manufactured for the cold-blooded, sometimes cannibalistic character of James Delaney?

Going back to the Renaissance, his music is built on the interval of a tritone. The tritone is the flat fifth. In renaissance theory, that was called “Diabolus in musica”, which translates to the devil in music. It’s because it has this destabilizing effect. It doesn't fit into major key properly, and the bass is like the whole tenth scale, diminished chords, and all these murky, dark corners of harmony. So, I built all his music around that — it really emphasizes that. And then, he had this other music, which is built around a lament bass. A lament bass is, again, a historical form, which is a falling bass line. Delaney's sad music has this lamenting bass line, which just descends all the time. His music is all about instability and falling. That’s kind of how his music is built, while at the same time, everything is turned up to 11.

In terms of the lamenting bass, how do you create that sensation of falling? I’m thinking of electric bass, and once you’re down to a low E, where would you go from there?

There's a couple of ways you can make it feel like it's falling all the time, which is something a lot of composers have worked with as well. What's the easiest way to explain it? Basically, you use octave transposition to make it feel like it continues to fall all the time. You know, the very famous bass line of Bach’s Air on the G String. It just feels like it’s falling all the time, but it isn’t. Because you’d run out of notes down there, you can do all sorts of tricks to make things appear to be moving in one direction, and another without them actually doing that.

L’Amica Geniale, also known as My Brilliant Friend, takes place throughout 60 years, beginning in a Neapolitan slum in the '50s. After the unexplained disappearance of her lifelong friend, an elderly woman reflects on her past, examining the complex layers of female companionship. What themes from Elena Ferrante’s tome guided your writing process for this limited series? To what extent did Italian cultural history factor into your musical treatment?

My Brilliant Friend is about a relationship. It's about two people whose connection starts in childhood and it goes through their entire life, so there's a kind of polarity in the music for My Brilliant Friend. That comes out most obviously in a lot of the piano music — a piano duet, two players. So, you've got these two characters inhabiting the keyboard. The other starting point for the music for My Brilliant Friend is a very famous traditional tune called La Follia, which is from a Mediterranean region. I borrowed it as a theme and then heavily disguised it, repurposing it as a part of the melodic texture for the show. We sort of recognize it, and it creeps up on our subconscious. Those are the two main things for My Brilliant Friend.

As well as the original music in My Brilliant Friend, there's a lot of music from my solo albums in the film. There's a lot of Vivaldi Recomposed. There's a lot of bits and pieces from Sleep. There are things from The Blue Notebooks. They've used a lot of material from my earlier work. It’s a hybrid score, really.

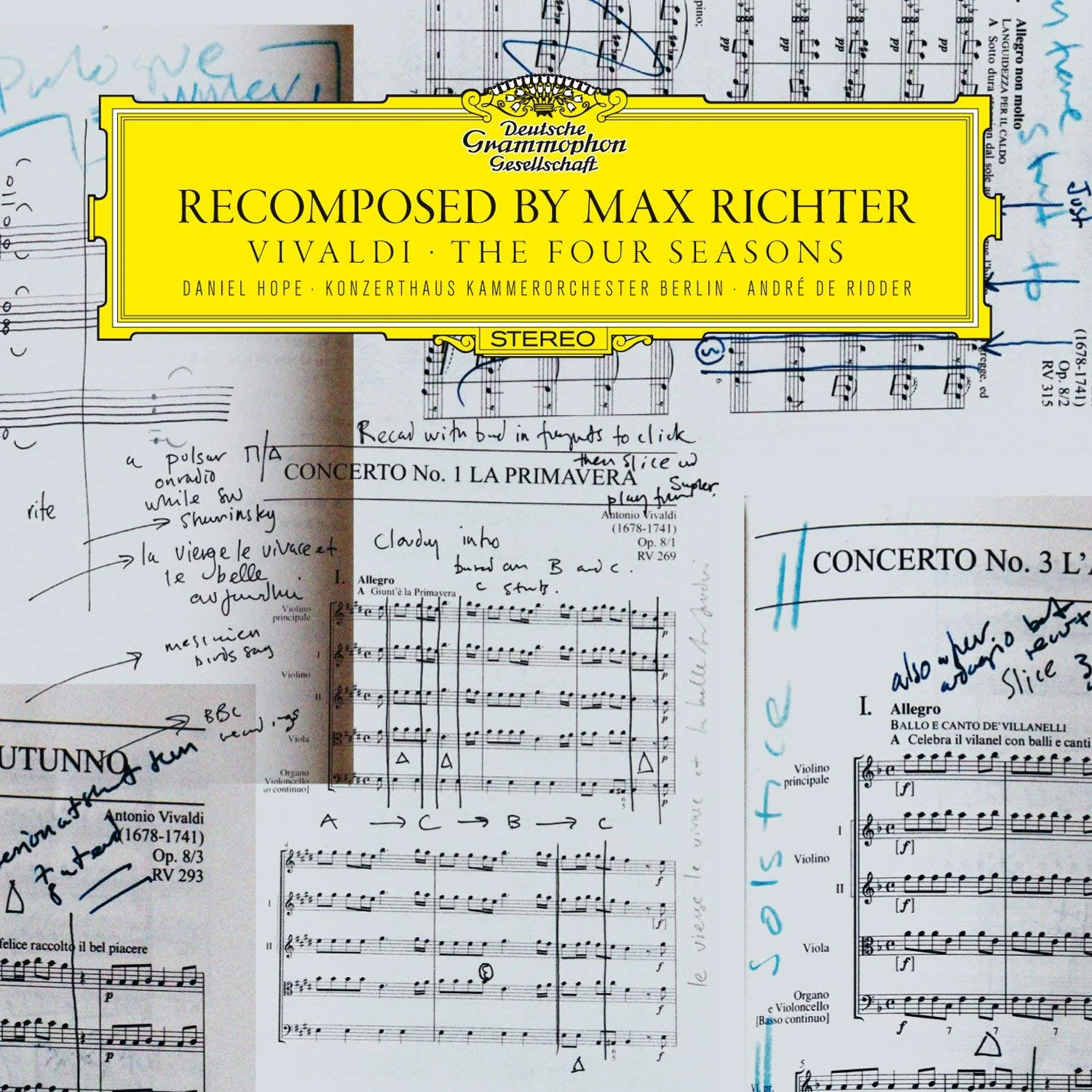

Speaking of Vivaldi and your album that reimagines The Four Seasons, what was the vision behind it? Upon listening, the work of Vivaldi is hard to recognize.

It's a real mix of processes. At a fundamental level, I see it almost like a remix. When you're remixing, you do all sorts of sculptural processes onto the original material. You're cutting it up, and looping, and reversing, and time stretching. Well, I did all of those things, but I did them on a piece of paper with Vivaldi's original notes, and then I re-recorded that score from scratch with an orchestra. That was my process. So, it's remixed, but it's remixed on paper. 75% of Vivaldi's notes are gone, and they've been replaced by my time stretched, looped, cut up, reversed, pitch-shifted new material, but all of it is played by the orchestra.

It’s scored from beginning to end on the page, but those original Vivaldi notes have been either reshaped, or they've been obliterated by new material which I've written. There are bits where you’re hearing only Vivaldi. There are bits where you’re hearing only me. Most of the time, you hear something in between those two extremes. There are four concertos, one for each season. Each concerto has three sections in it. It's the way the original Vivaldi works, so I just copied that structure from him.

The Leftovers was a magnificent series which centered around a fictional event called "Sudden Departure" in which 2% of the world's population vanished unexpectedly, leaving their loved ones to pick up the pieces and search for the truth. Thematically, it was a revolving door of loss, faith, and grief. Over the course of three seasons, what opportunities did this disturbing, paranormal narrative present?

The Leftovers was a wonderful project — an incredible piece of writing and filmmaking from Damon, Tom, and all the guys. What drew me into it was the emotional storytelling of the show and the fact that really everyone in it is trying to find an accommodation with this unknowable thing. Whether we’re in a TV show or not, we’re all trying to do that, right? It’s universal.

The image of the departure for me was really fascinating. It basically gave me my starting point for the kind of music I wanted to write and gave me the sense of the type of instrumentation I wanted to use. I decided to try and mirror this idea of departing by almost only using instruments with sounds that decay — pianos, chimes, bells, things which don’t really have a sustained tone. This image of the departure, of things going away, is embodied in the music in a quite profound way because all the instruments are piano tones. They don’t sustain; they do go away. I mean, there are all kinds of sounds. There’s pedal steel guitar, there are drums, all sorts of the colors, but overall, the big themes in The Leftovers involve piano, harp, and instruments that don’t have a sustained tone in their nature.

Your project, Sleep is an 8 1/2 hour sonic experience, designed to help people disengage from technological stimulation and indulge in a full night’s rest. What was the impetus behind this ambitious undertaking? Can you explain the scientific basis for the music you created?

This is going back to 2014 now, but my starting point for Sleep was a realization, really. My intuition, as a species, is that we’re a bit data-saturated and worn out by our 24/7 way of living — on the screens all the time, on social media all the time. We have to curate information all the time, and it seemed to me that it takes quite a psychological tool. Of course, five years have gone by, and it’s quite a lot worse now, but that was my feeling. I wanted to make a piece which, first of all, could act as a kind of a holiday — a mini holiday from that world. Secondly, as an act of resistance, a protest against that situation. I’m very interested in the political aspects of music making, the political aspects of creative teams. That's always been part of what I do. So, for me, this was like drawing a line in the sand and just going, "You know what? There's going to be eight hours where you're doing something else." A no Facebook thing for eight hours, which seemed to me would be very interesting.

The piece acts as a pause button, in a way that if you're reading a novel, or if you're looking at a painting you love or watching a movie, you're transported somewhere else away from the immediate chiming and bleeping screens that we continuously have around us. I wanted to make a piece which could function as a rest. That was really what it was about.

Time and time again, you have conjured forth music that transports your audience into hypnotic, trance-like registers of feeling. What music has this effect on you?

A lot of different kinds of music. I mean, I love Renaissance music. I love Elizabethan music. This music which transports you somewhere. I love a lot of electronic music, ambient music, all kinds of sounds, you know? I'm always looking. I've always got my ear open to new things.

What can we expect from your score for the upcoming futuristic sci-fi feature, Ad Astra?

Well, I'm very excited about it. It's a beautiful film. Just beautiful, beautiful storytelling. James [Gray, director of Ad Astra] and Brad [Pitt, producer and lead actor of Ad Astra] have done wonderful work on it. I've developed some new musical instruments for the score, which will operate in a way which I don't think has been done before, and I'm very excited about that. I can't really talk about them in any detail, I'm afraid, but it’s going to be special.

Interviewer | Paul Goldowitz

Research, Editing, Copy, Layout | Ruby Gartenberg

Extending gratitude to Max Richter and Costa Communications.